JA4+ Network Fingerprinting

TL;DR

In this blog I go over the new JA4+ network fingerprinting methods and examples of what they can detect.

JA4+ provides a suite of modular network fingerprints that are easy to use and easy to share, replacing the JA3 TLS fingerprinting standard from 2017. These methods are both human and machine readable to facilitate more effective threat-hunting and analysis. The use-cases for these fingerprints include scanning for threat actors, malware detection, session hijacking prevention, compliance automation, location tracking, DDoS detection, grouping of threat actors, reverse shell detection, and many more.

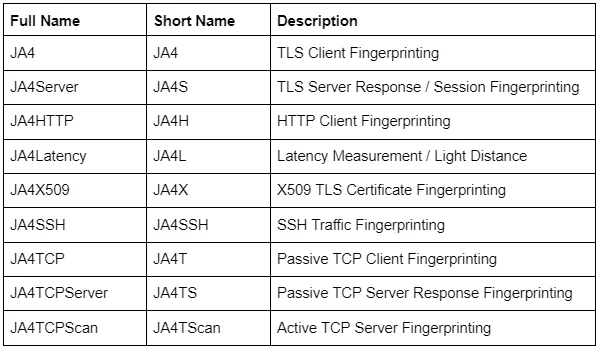

JA4+ Fingerprints:

More fingerprints are in development and will be added to the JA4+ family as they are released.

UPDATE: Click here for the JA4T/S/Scan — TCP Fingerprinting blog.

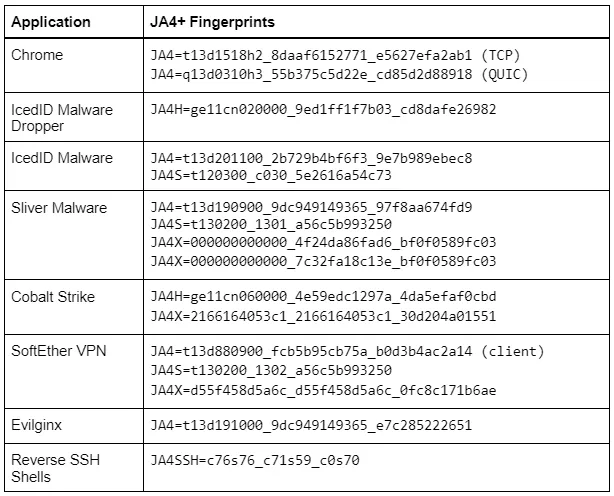

Examples:

JA4+ is available here: https://github.com/FoxIO-LLC/ja4

What is JA4+

JA4+ is a set of simple yet powerful network fingerprints for multiple protocols that are both human and machine readable, facilitating improved threat-hunting and security analysis. If you are unfamiliar with network fingerprinting, I encourage you to read my blogs releasing JA3 here, JARM here, and this excellent blog by Fastly on the State of TLS Fingerprinting which outlines the history of the aforementioned along with their problems. JA4+ brings dedicated support, keeping the methods up-to-date as the industry changes. Additionally, and by popular demand, an official JA4+ database of fingerprints, associated applications and recommended detection logic is in the process of being built.

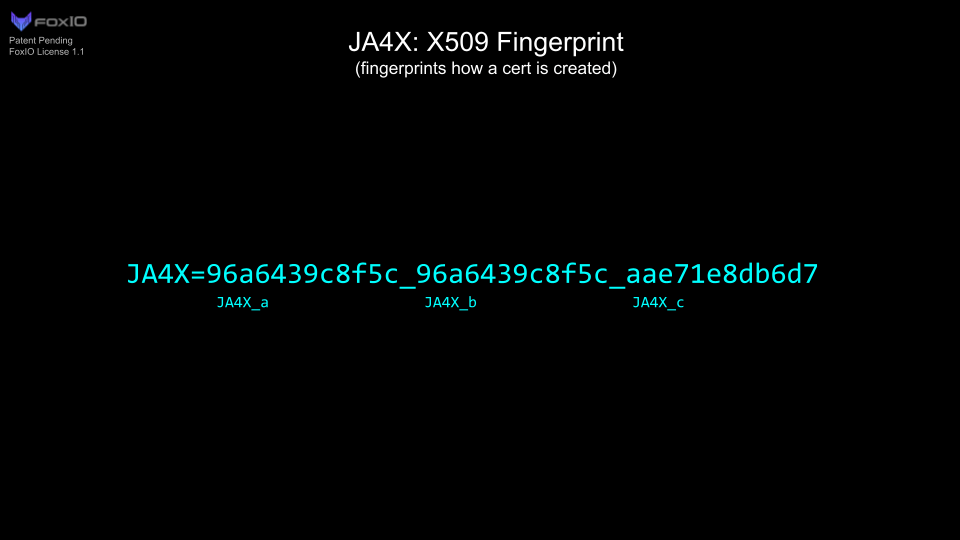

All JA4+ fingerprints have an a_b_c format, delimiting the different sections that make up the fingerprint. This allows for hunting and detection utilizing just ab or ac or c only. If one wanted to just do analysis on incoming cookies into their app, they would look at JA4H_c only. This new locality-preserving format facilitates deeper and richer analysis while remaining simple, easy to use, and allowing for extensibility.

In this blog we are releasing JA4/S/H/L/X/SSH, or JA4+ for short. More fingerprints are in development and will be added to the JA4+ family as they are released.

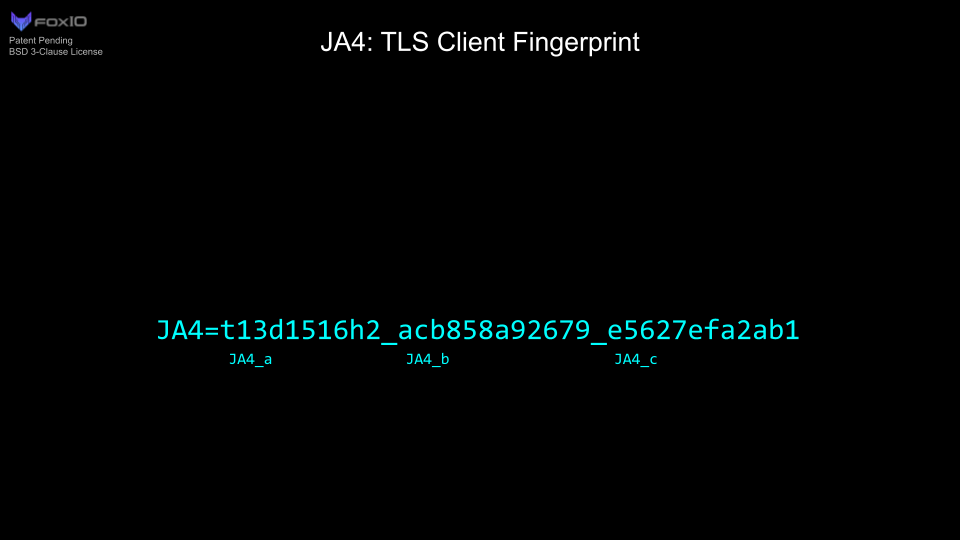

JA4: TLS Client Fingerprint

TLS is used to encrypt the vast majority of traffic on the internet, from web browsing to streaming, to IoT usage analytics. Even malware uses TLS to hide its malicious communications. At the beginning of a TLS connection, the client sends a TLS Client Hello packet which is sent in the clear, prior to encrypted communication. This packet, generated by the client application, informs the server of what ciphers it supports as well as its preferred method of communication. As such, the TLS Client Hello packet is unique per application or its underlying TLS library.

JA4 looks at this TLS Client Hello packet and builds out an easily understandable and shareable fingerprint. The format is as follows:

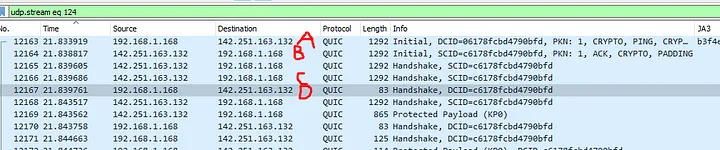

JA4 fingerprints the client, no matter if the traffic is over TCP or QUIC. QUIC is the protocol used by the new HTTP/3 standard that encapsulates TLS 1.3 into UDP packets. As QUIC was developed by Google, if an organization heavily utilizes Google products, QUIC could make up half of their network traffic, so this is important to capture.

JA4 also clearly shows the ALPN (Application-Layer Protocol Negotiation). This represents the protocol that the application wants to communicate in after the TLS negotiation is complete. “h2” = HTTP/2, “h1” = HTTP/1.1, “dt” = DNS-over-TLS, etc. A full list of possible ALPNs can be found here. A “00” here denotes the lack of ALPN. Note that the presence of ALPN “h2” does not indicate a browser as many IoT devices communicate over HTTP/2. However, the lack of an ALPN may indicate that the client is not a web browser.

More technical details for implementation and what the raw (unhashed) fingerprint looks like can be found on the github page.

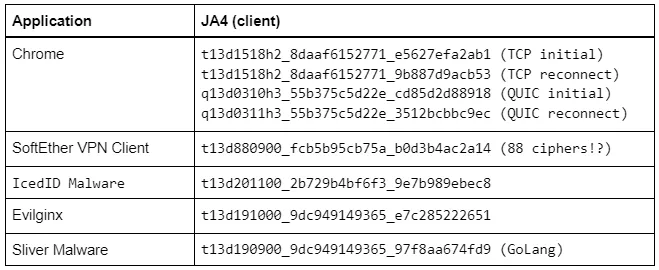

Even though the traffic is encrypted over TLS 1.3, we are still able to gain a huge amount of valuable information about the client application. Remember that most custom applications will have the fingerprint of their underlying TLS libraries. So a program written in Go will likely have a JA4 that matches other Go programs. The same is true for Python, Java, etc., while custom programs like VPN clients, Steam, Slack, and Windows functions will be unique.

JA4 can be extremely valuable in production networks where applications are largely static. If you are running an all Linux infrastructure, then a Windows JA4 fingerprint would be worth looking into. If you’re running only Exchange servers, then a sudden python JA4 fingerprint would be worth looking into. JA4 makes for a great pivot point in analysis when trying to understand network traffic and the a_b_c format allows for deeper analysis.

For example; GreyNoise is an internet listener that identifies internet scanners and is implementing JA4+ into their product. They have an actor who scans the internet with a constantly changing single TLS cipher. This generates a massive amount of completely different JA3 fingerprints but with JA4, only the b part of the JA4 fingerprint changes, parts a and c remain the same. As such, GreyNoise can track the actor by looking at the JA4_ac fingerprint (joining a+c, dropping b).

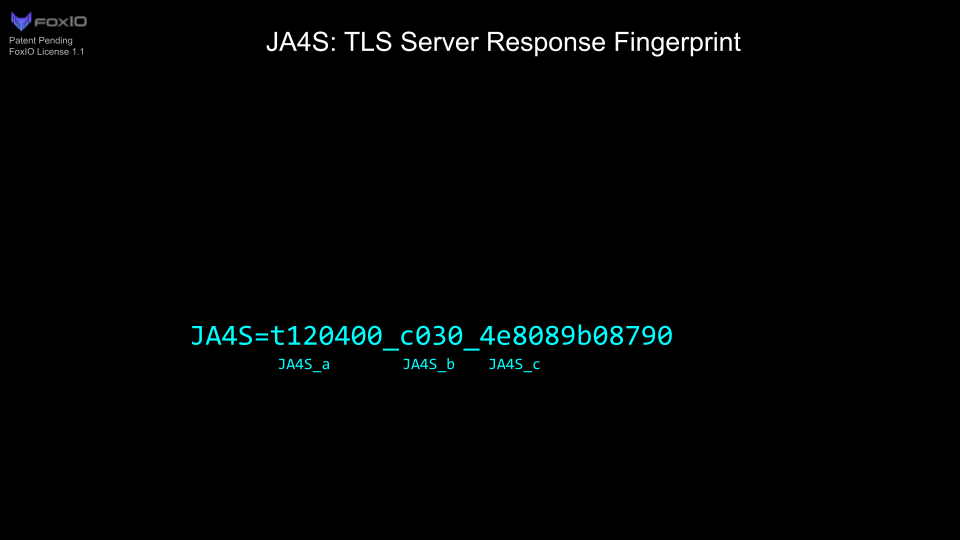

JA4S: TLS Server/Session Fingerprint

After a client sends its TLS Client Hello packet, the server will respond with its TLS Server Hello packet. This packet, also sent in the clear, is formulated based on the server’s selection of available options in the Client Hello. This includes the one cipher chosen out of the list of available options, and any extensions the server wishes to set.

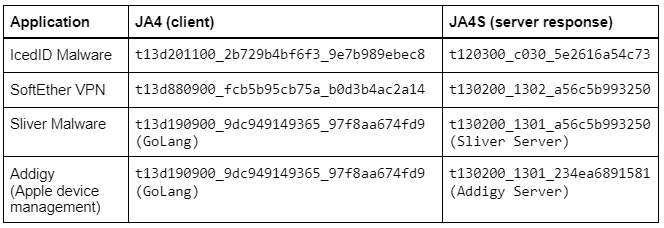

As such, the Server Hello is unique to both the server application and the Client Hello that was sent to it. A different Client Hello may cause a different Server Hello, and therefore a different JA4S, from the same server. However, the same Client Hello will always produce the same Server Hello from that server application. For example if the client sends JA4=a_b_c and the server responds with JA4S=d_b_e, that server will always respond to a_b_c with d_b_e. But if another application sends a different client hello to that same server, say JA4=x_y_z, the server will respond with a different server hello, JA4S=t_y_v. So it’s a different response to different applications but always the same response to the same application. I go into more detail on this in my JA3S blog post.

JA4S, when combined with JA4, significantly increases detection fidelity. Going from merely identifying underlying libraries of a client to identifying the client or malware family. Beyond application identification, one could look at just JA4S_b to understand what ciphers are being used on any given network to ensure it is meeting compliance requirements. All of this is possible without breaking encryption.

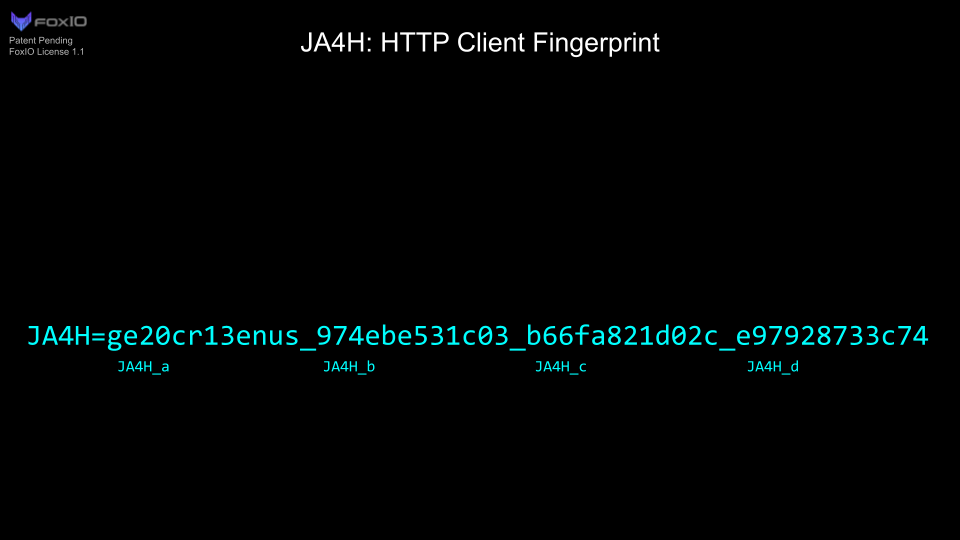

JA4H: HTTP Client Fingerprint

JA4H fingerprints the HTTP client based on each HTTP request. As most traffic is encrypted, JA4H is best utilized on servers, proxies, WAFs, TLS terminating load balancers, and environments where TLS is decrypted. However, JA4H is still valuable even in environments where TLS is not decrypted because a lot of devices and programs, including malware, still communicate over HTTP. The IcedID malware dropper, for example, doesn’t use TLS. These malware programs are very easy to fingerprint.

JA4H_ab are a fingerprint of the application for the given HTTP method used. The lack of an Accept-Language is a clear indication that the application is not human interactive, ergo a bot.

JA4H_c is a fingerprint of the cookie and will be different for each website visited but will be the same for that website or application. For example, every Plex server or Okta server will produce the same JA4H_c.

JA4H_d is a fingerprint of the user and will be different per user. This allows for tracking of a user through a website without logging SPII, thereby keeping the logging system GDPR compliant.

More details on the technical implementation can be found on our github.

On the server side, one could use JA4H_c as a hunting method. As the server is specifying which cookie fields the client should use, all clients should have the same JA4H_c. Discrepancies here merit looking into. One could also track a user with JA4H_d and their client application with JA4H_ab or identify bots with just JA4H_ab.

On the client side (proxy, NDR, zero trust), JA4H combined with JA4 and JA4S allow for extremely high fidelity application and malware detection.

There are a lot of use cases for JA4H, especially when combined with the rest of JA4+. I’ll cover all of them in more detail in a later blog post.

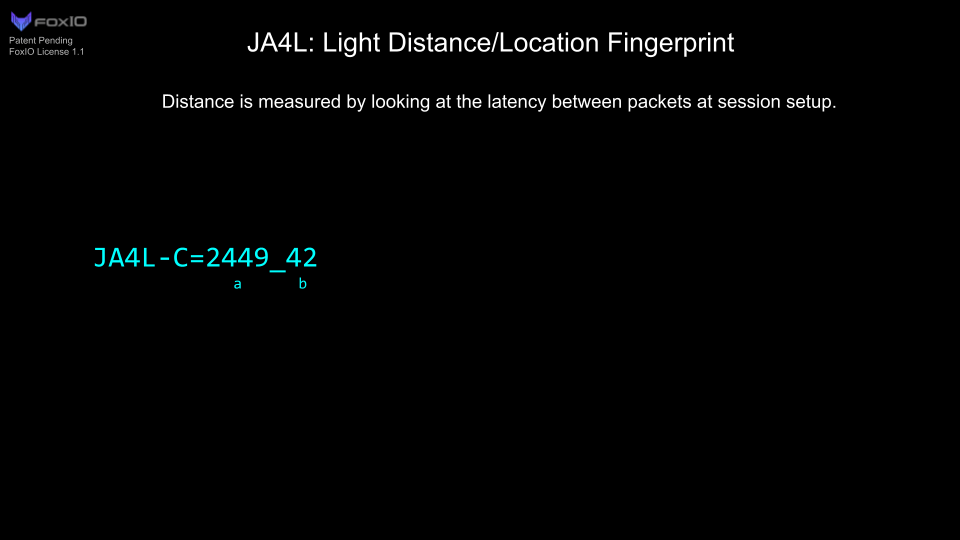

JA4L: Light Distance Locality

JA4L measures the distance between a client and a server by looking at the latency between the first few packets in a connection. We use the first few packets because these are low-level machine generated, so there is nearly zero processing delay in creating and sending these packets. Time is measured in microseconds (µs), 1ms = 1000µs, as microseconds are a standard unit of time measurement in packet captures.

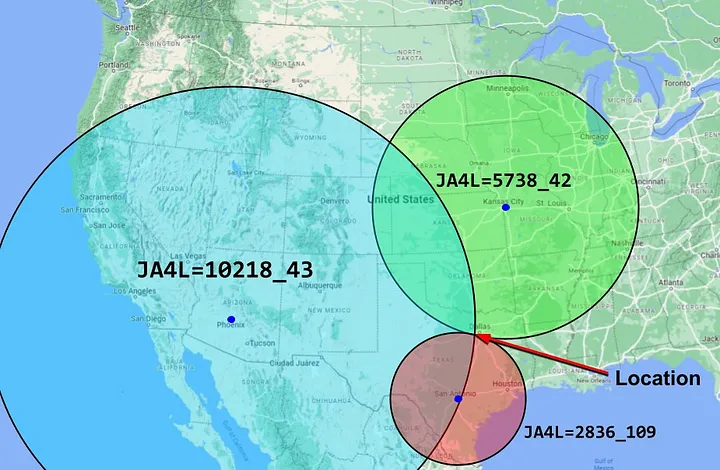

If JA4L is running server side, this will measure the distance of the client from the server and if this is running client side, this will measure the distance of the server from the client. If this is running on a network tap, it will measure the distance of each from the network tap location.

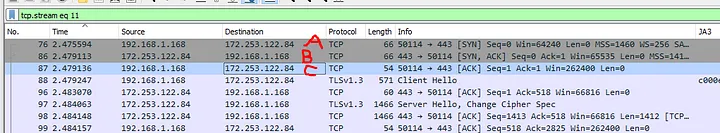

JA4L is split up into 2 measurements, client and server. For TCP, these are determined by looking at the TCP 3-way handshake. UDP, we’re looking at the QUIC handshake.

JA4L-C = {(C-B)/2}_Client TTL

JA4L-S = {(B-A)/2}_Server TTL

In the above example:

JA4L-C = 11_128

JA4L-S = 1759_42

JA4L-C = {(D-C)/2}_Client TTL

JA4L-S = {(B-A)/2}_Server TTL

In the above example:

JA4L-C = 37_128

JA4L-S = 2449_42\

Distance Measurement:

With JA4L we can determine the distance between the client and server using this formula:

D = jc/p

D = Distance

j = JA4L_a

c = Speed of light per µs in fiber (0.128 miles/µs or 0.206km/µs)

p = Propagation delay factor

Typical propagation delay depends on terrain and how many networks are involved.

Poor terrain factor = 2 (around mountains, water)

Good terrain factor = 1.5 (along highway, under sea cables)

SpaceX factor = … needs to be tested

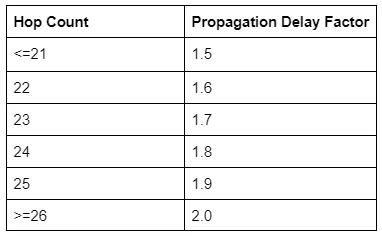

We can use the TTL to calculate the hop count, which can help inform the propagation delay factor. (The table below is a good starting point but more testing needs to be done.)

To calculate the number of hops a connection went through, subtract the TTL from its estimated initial TTL.

Cisco, F5, most networking devices use a TTL of 255

Windows uses a TTL of 128

Mac, Linux, phones, and IoT devices use a TTL of 64

Most routes on the Internet have less than 64 hops. Therefore if the observed TTL, JA4L_b, is <64, the estimated initial TTL is 64. Within 65–128, the estimated initial TTL is 128. And if the TTL is >128 then the estimated initial TTL is 255.

With a JA4L-S of 2449_42, the observed TTL of 42 means the initial TTL was likely 64, a Linux server. 64-42 gives us a hop count of 22.

2449x0.128/1.6=195

We can conclude that this server is within 195 miles of the client. The server may be closer than this, but it is physically impossible for it to be farther away as the speed of light is constant. If there are multiple JA4Ls for the same host, the lowest value should be taken as the most accurate.

In this example, the actual distance was 194 miles.

Utilizing multiple locations, one can passively triangulate the physical location of any client or server down to a city area. More on this in a later blog post…

Additionally, JA4L_b (TTL) passively facilitates the identification of source operating systems which is an excellent data point to have when performing forensic analysis. Also, because JA4L is looking at Layer 3 data, it works on encrypted and unencrypted traffic.

Combining JA4 with JA4H and JA4L on the server side makes it possible for the server application to identify session hijacking or MiTM attacks. If a session cookie (JA4H_d) were to suddenly change locations, operating systems (JA4L), and application (JA4 and JA4H_ab), then it would make sense to revoke the session token, asking the user to log back in with MFA. With this type of logic, special care should be taken to not allowlist particular fingerprints as applications will change over time, but instead to look for dramatic changes. Session hijacking detection with JA4+ is something darksail.ai is working on right now.

JA4X: X509 TLS Certificate Fingerprinting

Credit: W.

JA4X fingerprints the way in which TLS certificates are generated — not the values within the certificate. This can identify applications and settings used to create the certificate which can be extremely useful in threat hunting as threat actors will create different certificates but tend to use the same methods to create said certificates, thereby having the same JA4X fingerprint.

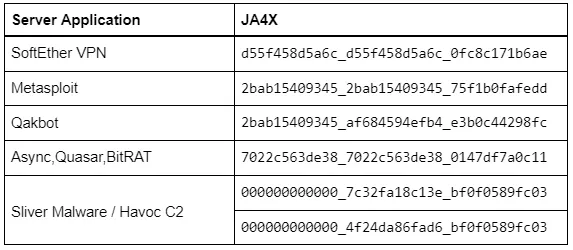

SoftEther VPN was heavily utilized by Chinese APT actors, Flax Typhoon, to compromise Taiwan infrastructure, and Storm-0558 in the hacking of US Government Email accounts. According to Microsoft, it is very difficult to differentiate these connections from legitimate HTTPS traffic. However, because of the programmatic way that SoftEther generates its certificates, the JA4X is unique to SoftEther. If JA4X were to be implemented into a firewall, blocking traffic to SoftEther VPNs would be trivial. And by utilizing a JA4X feed, blocking inbound traffic from SoftEther VPNs would be trivial as well.

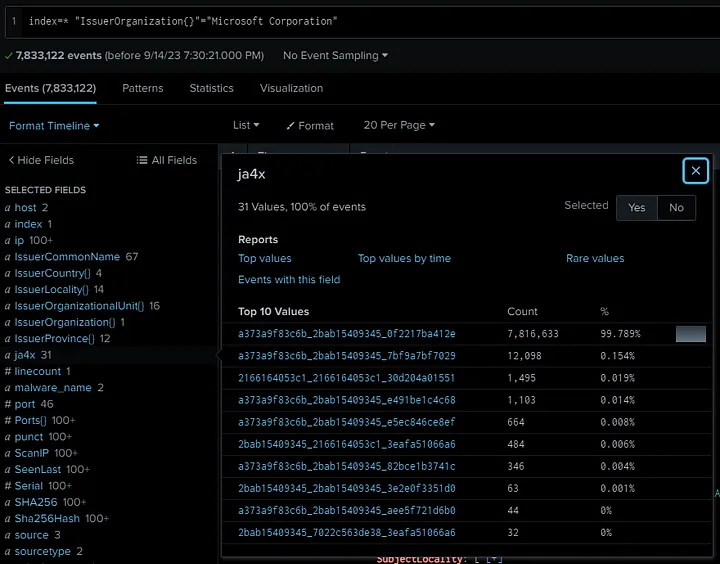

Most certificate issuing organizations will use the same underlying program to generate and sign all of their certificates. Using Internet scan data enriched with JA4X from our friends at Hunt.io, we can take a look at Issuer Organization = “Microsoft Corporation” as an example.

You can see that 99.8% of observed certificates have the same JA4X. The next one down is very similar, but the third one looks completely different. Let’s pivot on this anomaly.

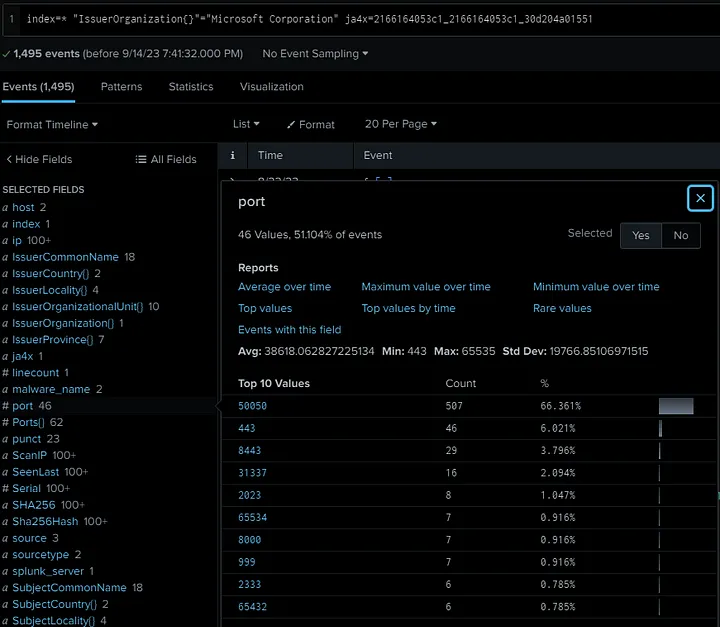

Oh look, it’s all Cobalt Strike! Well, that was easy.

Hunting with JA4X on Internet scan data is extremely powerful because rather than looking at the values within a certificate, which, in the case of malware, are usually randomly generated, JA4X looks at how the certificate was generated.

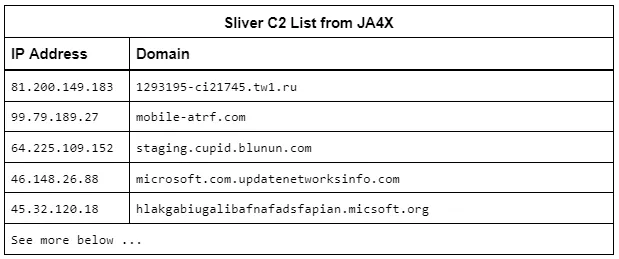

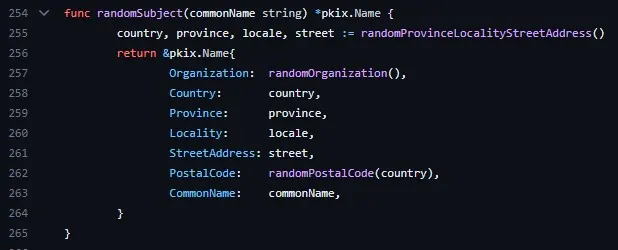

One final example is Sliver C2, which is a newer pentesting framework that is replacing Cobalt Strike in popularity. Like most good pentesting frameworks, Sliver is also heavily utilized by threat actors as it is designed to be difficult to detect.

Sliver has over 400 lines of code dedicated to randomly generating TLS certificates. As such, each certificate is unique and pivoting on a certificate hash will yield no results.

However, each certificate is also generated by the same application and therefore has the same JA4X. Havoc C2 uses most of the Sliver code so it too has the same JA4X, but can be differentiated by looking at the Org Name and Postal Code length. In either case, both are malware and the JA4X is unique on the Internet. Our friends at driftnet.io offer a JA4X feed and, with it, were able to quickly identify all default Sliver C2s listening on the Internet.

These examples show how JA4X can be used to detect and block traffic to SoftEther, Tor, Metasploit, Sliver, Havoc, RAT C2s, etc. Note that TLS certificates are sent in the clear in TLS 1.2, but are encrypted in TLS 1.3 so JA4X is best utilized on Proxy servers, Firewalls, MDR, NDR and Zero Trust applications that have that level of inspection. JA4X, when combined with JA4, JA4S, JA4H and JA4L provides an unparalleled level of visibility and detection capability. When used in internet scanning, JA4X is an excellent tool for pivot analysis and hunting down malicious servers, especially when combined with JARM data.

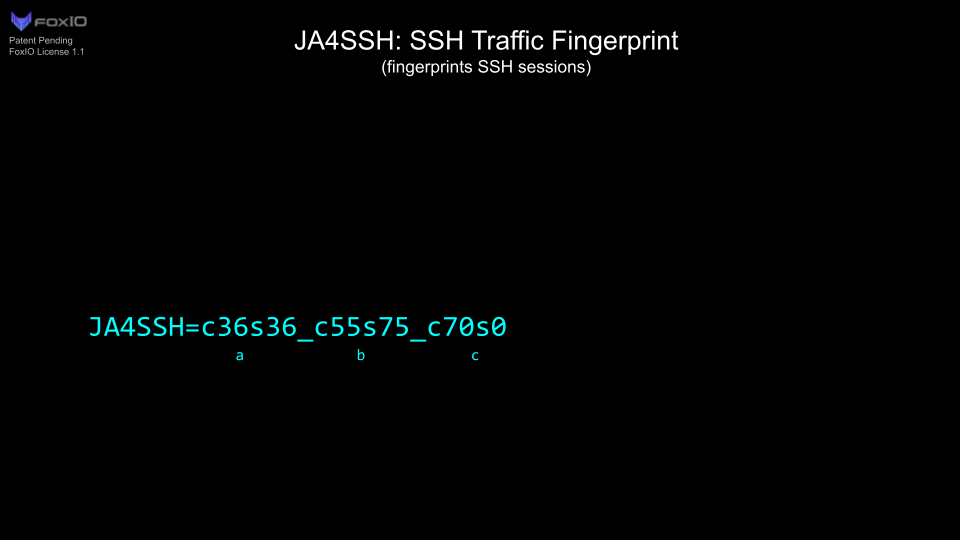

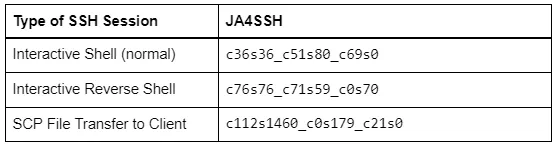

JA4SSH: SSH Traffic Fingerprinting

JA4SSH fingerprints SSH sessions by looking at SSH packets and providing a small, simple, easy-to-read fingerprint of the session on a configurable rolling basis, every 200 packets by default. With this, we are able to determine what is happening within the SSH connection, even though the traffic is encrypted, and provide an analyst with a simple set of fingerprints for their analysis.

Note that JA4SSH fingerprints the SSH session, not the SSH applications. For SSH application fingerprinting, I recommend you take a look at HASSH, by my good friend Ben Reardon.

To understand how SSH traffic works and how to identify tunnels using traffic analysis, I recommend you read these excellent blogs on the subject by Trisul.org here and here.

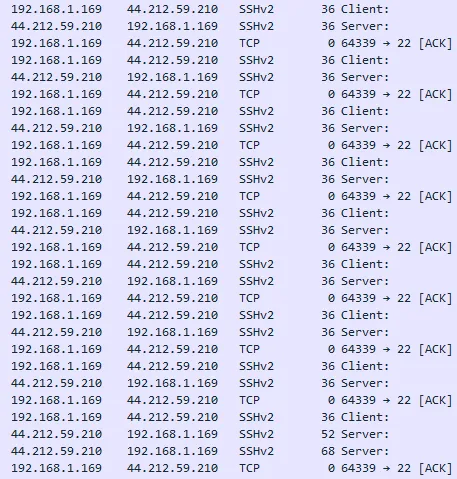

In short, SSH packets are padded out to a particular length depending on the cipher algorithm and HMAC used. With chacha20-poly1305, that ends up being 36 bytes. When the client types a character into the ssh terminal, that character is encrypted with the packet padded to 36 bytes and then sent to the server. The server will respond with the same character in a 36 byte packet and that’s when the character is displayed in the terminal window. The client will then send a TCP ACK packet to tell the server that they’re done with the previous transaction. Because of this, a client typing in a terminal will look like this:

Notice that the TCP ACKs are coming from the side doing the SSH requests (client) and the server returns the output of the command at the bottom. The JA4SSH for this looks like: c36s36_c51s80_c69s0. So you see 36/36 and all the ACKs are from the client, the server has sent none, so from these we can easily see that it is an interactive forward SSH session.

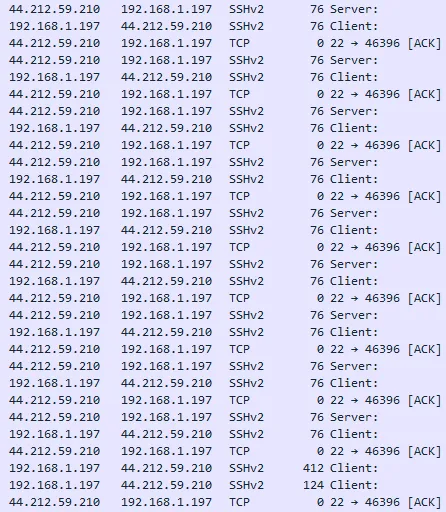

In a reverse SSH shell, it’s SSH over SSH so the packets are double padded + HMAC. Here’s what it looks like:

The JA4SSH for this looks like: c76s76_c71s59_c0s70. We can clearly see a common packet length of 76/76, double padded, and all of the ACKs are coming from the server, meaning it is the server side that is doing the typing. It’s important to note that SSH provides encrypted messages, not an encrypted tunnel, so layer 4 packets, the TCP ACK packets, are sent in the clear. It is with these that we are able to determine which side is initiating the requests. By utilizing JA4SSH, it is now trivial to detect reverse SSH shells.

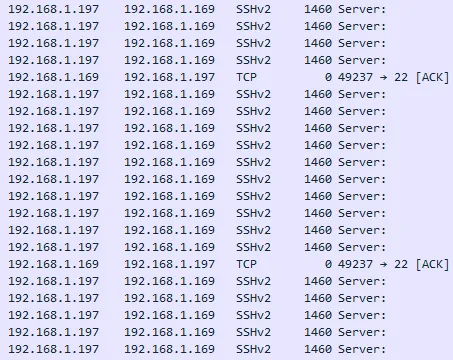

In a SCP file transfer, the TCP Length is maxed out and looks like:

The JA4SH for this looks like: c112s1460_c0s179_c21s0. Notice the maxed out window of s1460, that all SSH packets are coming from the server and all TCP ACK packets are coming from the client. This easily shows that the client requested a file and the server is sending it.

In static environments, like banks, where files are transferred over SFTP between the same systems every day, the JA4SH fingerprints of those connections should remain similar and any major deviation, such as looking like an interactive shell, would be worth alerting on.

JA4SSH makes it easy to detect certain types of SSH activity and delivers fingerprints in a format that is simple to understand. Combining JA4SSH with JA4L can inform the distance of the client/server as well as the operating system of each.

Licensing

JA4: TLS Client Fingerprinting is open-source, BSD 3-Clause, same as JA3. This allows any company or tool currently utilizing JA3 to immediately upgrade to JA4 without delay.

JA4S, JA4L, JA4H, JA4X, JA4SSH, and all future additions, (collectively referred to as JA4+) are licensed under the FoxIO License 1.1. This license is permissive for most use cases, including for academic and internal business purposes, but is not permissive for monetization. If, for example, a company would like to use JA4+ internally to help secure their own company, that is permitted. If, for example, a vendor would like to sell JA4+ fingerprinting as part of their product offering, they would need to request an OEM license from us.

JA4+ can and is being implemented into open source tools, see the License FAQ for details.

This licensing allows us to provide JA4+ to the world in a way that is open and immediately usable, but also provides us with a way to fund continued support, research into new methods, and the development of the upcoming JA4+ Database. We want everyone to have the ability to utilize JA4+ and are happy to work with vendors and open source projects to help make that happen.

Conclusion

JA4+ provides a suite of modular network fingerprints that are easy to use and easy to share. The use-cases for these fingerprints include scanning for threat actors, malware detection, session hijacking prevention, compliance automation, location tracking, DDoS detection, grouping of threat actors, reverse shell detection, and many more. JA4 (TLS Client Fingerprinting), is licensed under BSD 3-Clause, allowing tools running JA3 to immediately upgrade, while JA4+ (JA4S/L/H/X/SSH) is under the FoxIO License, which is permissive for most use cases except monetization, for that the vendor would need to purchase an OEM license which is what funds further research and the development of the JA4 database (coming soon). We plan to release a new JA4 method about once per quarter so stay tuned.

JA4+ is available here: https://github.com/FoxIO-LLC/ja4

For licensing or questions, reach out to us at www.fox-io.com

You can reach me directly on LinkedIn or Twitter/X.

JA4+ was created by:

John Althouse

With feedback from:

Josh Atkins

Jeff Atkinson

Joshua Alexander

W.

Joe Martin

Ben Higgins

Andrew Morris

Chris Ueland

Ben Schofield

Matthias Vallentin

Valeriy Vorotyntsev

Timothy Noel

Gary Lipsky

And engineers working at GreyNoise, Hunt, Google, ExtraHop, F5, Driftnet and others.